Don't Dream about Love, Kuryluk

06.05-14.08.2016

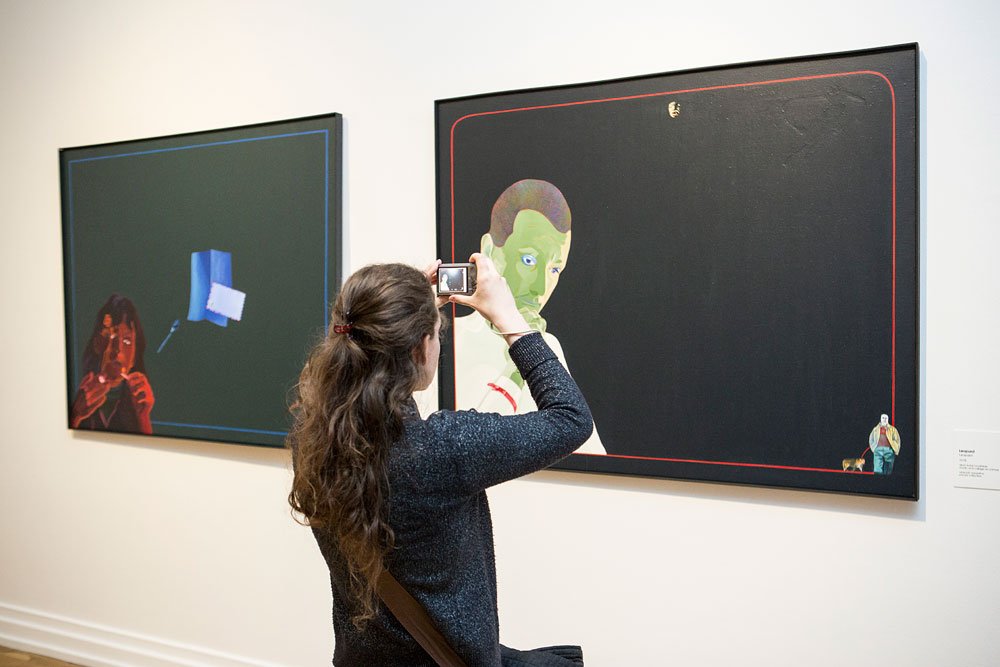

Don't Dream about Love, Kuryluk is a retrospective exhibition of paintings by Ewa Kuryluk, a painter, installation artist, art historian and writer. The show features over 50 paintings from the collections of the National Museum in Krakow, the National Museum in Warsaw, the National Museum in Wrocław and Museum of Art in Łódź, as well as important works from the artist's own collection to be presented in Poland for the first time.

EWA KURYLUK was born on 5 May 1946 in Krakow. Her father – Karol Kuryluk – was the founder and publisher of the pre-war Lviv "Sygnały" [Signals] and after the war became the editor of the weekly "Odrodzenie" [Revival], while her mother – Maria Kuryluk (b. Miriam Kohany) – was a writer and translator.

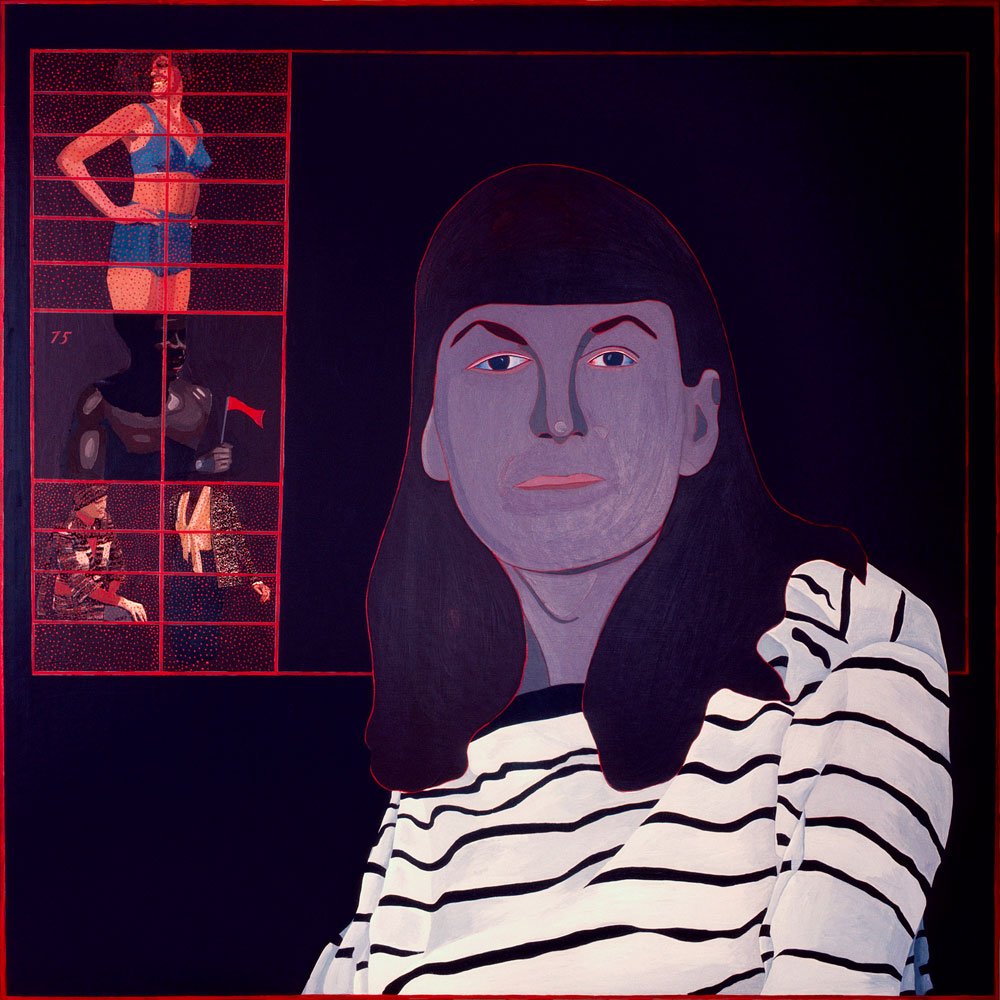

The exhibition at the National Museum in Krakow – the first Polish retrospective of Ewa Kuryluk’s paintings – begins with her self-portrait "Don’t Dream about Love, Kuryluk" (1977), and ends with her canvas "Helmut Mourning a Pheasant" (1967), which in 1969 opened her first solo exhibition at the Higher School of Music in Warsaw.

The exhibition constitutes an important summary of Kuryluk’s painting achievements. She admits that in the last forty years the world’s best collection of her paintings has been preserved at the National Museum in Krakow. The exhibition is held in its Main Building, located only about fifteen minutes away from the rotunda at no. 15 Basztowa street, where a little baby began to observe the world – the baby who on 5 May 2016, the day of the opening of the exhibition, will turn seventy.

In her paintings, the artist talks about herself in the world, and about the world within her. It is a specific, symbolic and surreal realism – Kuryluk willingly surrounds her self-portraits with cut-outs and collages. Yet she avoids self-interpretation and does not get sentimental over her manifold alter egos – she tends to mock them.

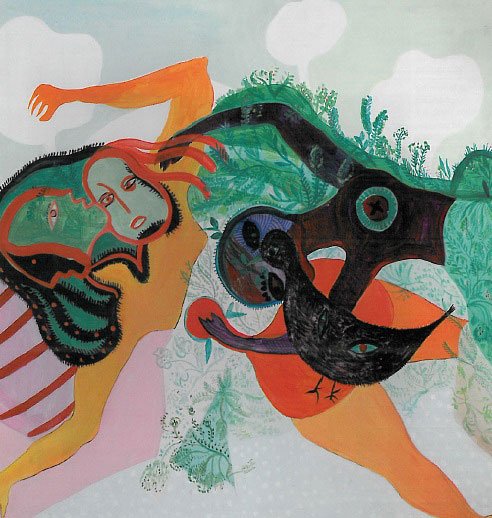

Before Ewa Kuryluk became part of the history of Polish and world hyperrealism, she had undergone an interesting evolution. The exhibition on display at the National Museum in Krakow, covering the years 1967–1978, perfectly illustrates these transformations. Her first mature cycle, which she titled "Human Landscapes", is permeated with romantic and poetic spirit of dreamlike visions, hidden symbols and meanings. In these paintings everything merges together and penetrates one another, people, plants and animals blend together and form humanoid landscapes, grotesque and often serene at first glance, but in fact full of terror. Young Kuryluk, standing on the threshold of her artistic challenges, treats each element of painting in the same way, expressing it through intense patches of colour and contour – often as red as a small vein, thin and sharp.

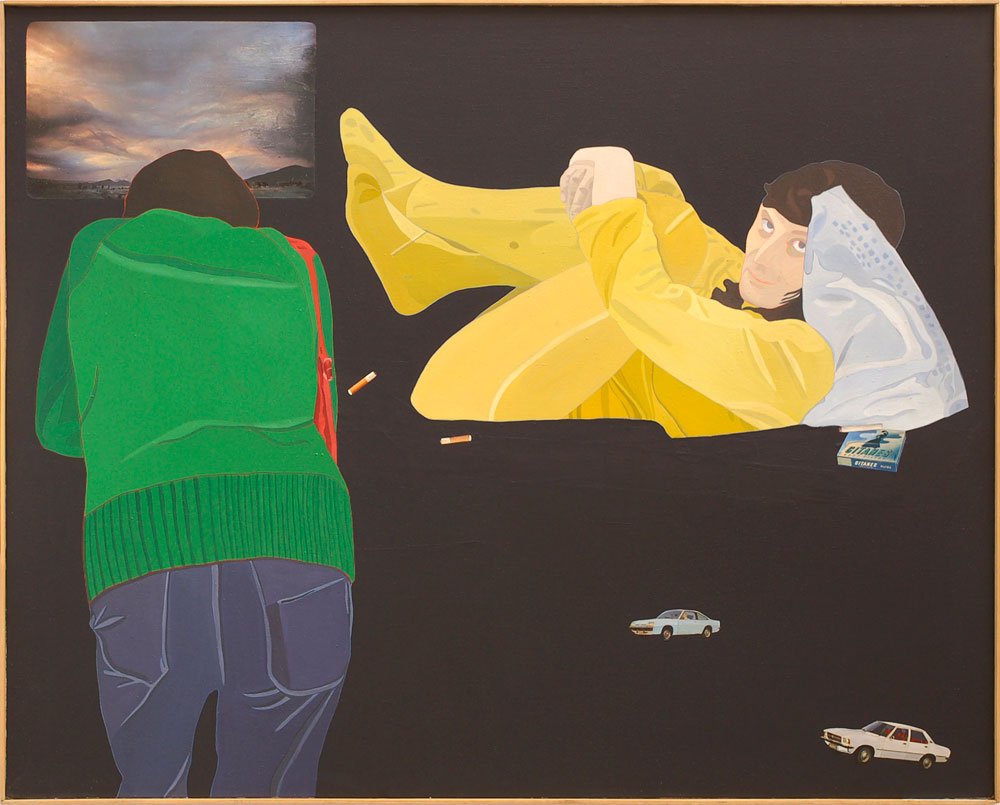

The next chapter in Ewa Kuryluk’s painting is "Screens", based on the dissonance between what is happening ‘outside’ and what takes place 'inside'. The first work in the series was "Execution" (1970), expressing the change in perception and experience of the world which invades our four walls when we turn on the TV. "Execution visually coexists here with the couple lying in bed, constituting the background of their private life, contrasting with it and determining its tone. The two aspects of reality – multidimensional and distant in time – become very close to each other. One can imagine the reversal of this scene – the dying are watching a love scene" (Kuryluk, Hiperrealizm – nowy realizm, Warszawa 1979, p. 189). In the following – photorealistic – period, the TV screen was replaced by a collage in the form of vignettes.

Focusing on the relationship between the real and the reflected world required changing the artist’s means of expression, accuracy and precision in recreating reality. At that time, Kuryluk became obsessed with the pursuit of concrete reality. To accomplish it, she began to browse through illustrated magazines, look at street advertising, analyze television programmes and movie shots. More and more often she would cut pictures from newspapers, magazines, posters and packaging to use them in her paintings in the form of collages.

The artist projected her own slides on the canvas to 'capture the phenomena eluding my perception: excessive movement and complex systems'. She wrote that in an era of increasing mobility, when we have less and less time for one another, 'a photograph enables the study of the body posture, gestures, facial expressions' (Kuryluk, "Hiperrealizm…", p. 190).

In the spring of 1978, Ewa Kuryluk was afraid that this was the end of her artistic journey. But it turned out to be a new beginning. After her departure from painting on canvas stretched on a frame, she began to draw and paint on loose surfaces, cotton canvas and silk, becoming a pioneer of ephemeral textile installations, based on outlining the shadow and oscillating between painting and relief. Photography became the basis for Ewa Kuryluk’s entire artistic activity – both visual and literary – in 1959, when her father gave her a camera with a self-timer. She took her first photos during a summer holiday, and thus her passion began, becoming more and more conscious and consistent as time went by. Thousands of photographs that have been created in the meantime, constitute her autobiography captured by the eye of the camera.

The period of nearly two years spent in London from the spring of 1977 to the autumn of 1978 is considered by the artist to be the best time in terms of painting. She cooperated with Fischer Fine Arts Gallery, which promoted hyperrealism and new figuration. It was in Little Venice, a district on the Hampstead canal, that the style of her paintings clarified and gained momentum, while the colours became more pastel and cool.

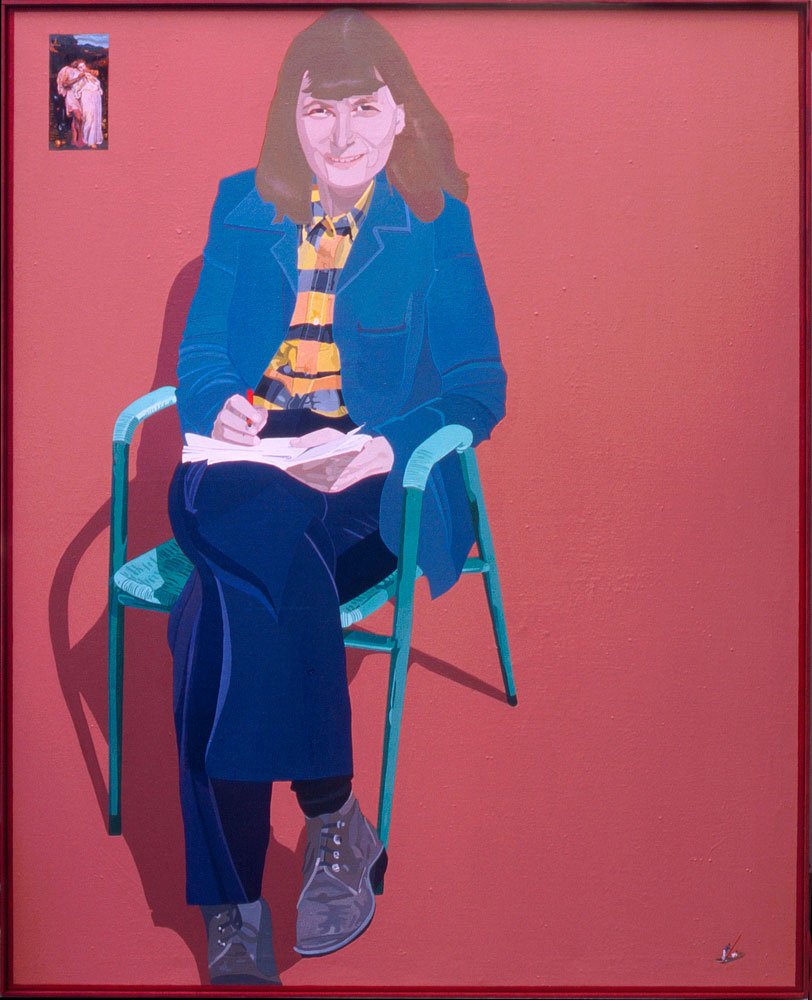

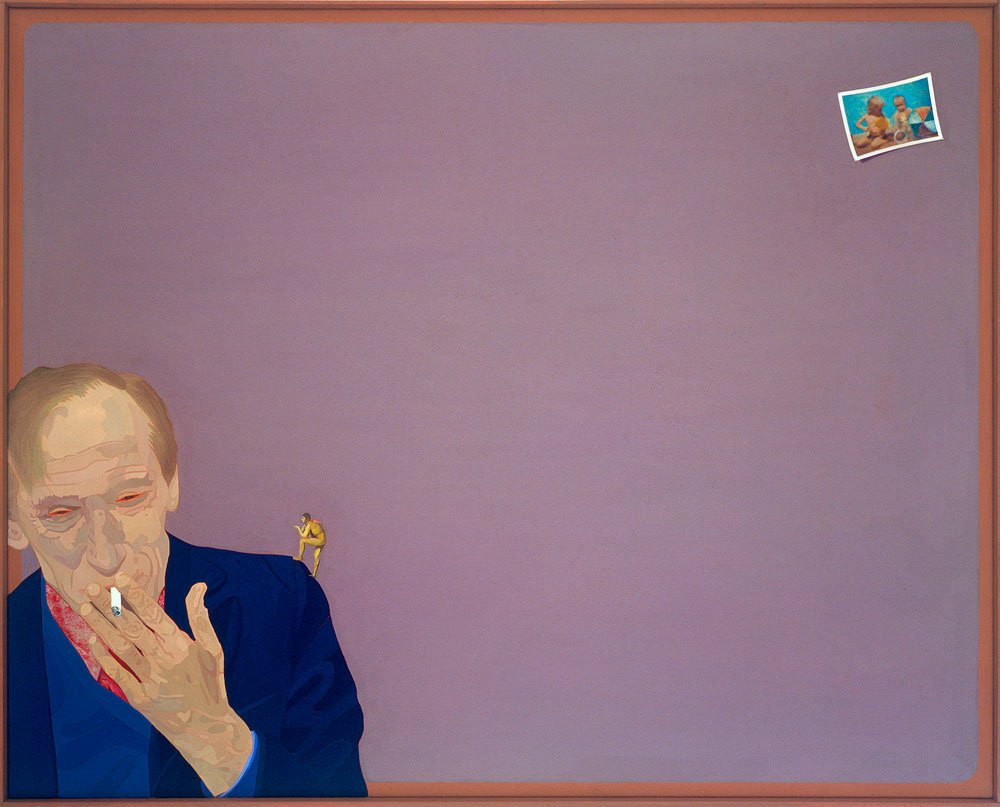

In the last period of her painting activity, Ewa Kuryluk used her own photographs, usually of herself, and projected the outline of the figures on canvas. The portrayed people – abstracted from reality and frozen as if they were photographed – appear against a homogeneous background: neutral, raw and dispassionate.

The artist examines herself, looks into the viewers eyes, or turns away from them. We see her different moods – joyful, focused, thoughtful, melancholic. What attracts our attention are the 'vignettes' – small and discreet 'fragments borrowed from another reality', usually placed in the corners of her paintings. Seemingly detached from the portrait, they evoke thoughts, memories, dreams. They do not directly correspond with the portrait itself, yet they enrich its reception. At this point we should take a closer look at the artist’s workshop, which is very important when talking about artists belonging to the photorealism genre.

Ewa Kuryluk implemented hyperrealism in her own way, not by copying photographs, but using them merely to cut the figures out of their background and to outline them precisely. It can be said then that she used to outline a shadow. She selected the right shot from her collection of mostly black and white slides, which she then projected onto the canvas in order to outline the figures with a pencil, separate the zones of light and shadow, and turn the illusion of three-dimensionality into a linear grid. If she preserved any elements of the figure’s surroundings at all, they were only small fragments: an edge of a table, an arm of a chair, a chain of a swing, or a typewriter. She covered the grid with flat patches of colour, brighter in the light and darker in the shade, and finally outlined it with a thin contour, usually a red line. The human figure – compressed like a plant in a herbarium – was placed on a flat homogeneous background. This unique way of working with photographs allowed the painter to develop her own original style, and at the same time enter the international trend of painting of the second half of the 20th century.

To conclude, Ewa Kuryluk’s painting is a reflection of her belief in the individual value of a human being, its uniqueness and significance. A person, isolated from his or her environment, stands in front of us as a one-of-a-kind, enigmatic creature. In "Human Landscapes", he or she blended with nature and came to the foreground in "Screens". In the last stage of Ewa Kuryluk’s art, the human being is the most important. The transition from the 'horror vacui' to 'amor vacui' seems to be immensely significant. This is how she gradually reached painting 'asceticism' and focused on the image of an individual – one and only in the entire history of humankind.

MNK The Main Building

al. 3 Maja 1 1st floor- Monday: closed

- Tuesday - Sunday: 10.00-18.00

1977, acrylic and collage on canvas

property: National Museum in Wrocław

1968, acrylic on board

1969, acrylic on board

1970, acrylic on board

1970, acrylic on board

1971, acrylic and collage on board

property: NMK

acrylic and collage on board

1976, acrylic and collage on canvas

1978, acrylic and collage on canvas

1976, acrylic and collage on canvas

1976, acrylic and collage on canvas

/ photo by Karol Kowalik - Photography Studio, NMK

/ photo by Karol Kowalik - Photography Studio, NMK

/ photo by Karol Kowalik - Photography Studio, NMK

/ photo by Karol Kowalik - Photography Studio, NMK

/ photo by Karol Kowalik - Photography Studio, NMK